Set out below is an excerpt from our June 2019 quarterly update to investors.

Please note that the information is suitable only for wholesale investors, as defined by the Australian Corporations Act.

Rare Earths

We wrote about rare earths in 2017 and at that time came to this conclusion: Whilst there is a strong likelihood that rare earths prices will take off over the coming years, there is currently sufficient uncertainty over timing that we will continue to monitor this market but are likely to restrict our investment to our current holding in Peak.

That decision was proven the correct one, as prices remained low and there were far better places to invest. However, over the past 3 months some rare earth companies have seen a more than doubling of their share prices as rare earth prices have risen on media speculation about China’s possible restriction. So, we ask the question again… Is it now time to invest?

Recent media speculation around China potentially restricting supply of rare earths has spiked prices up.

We have also seen the recent Wesfarmers bid for Lynas (the largest producer of rare earths outside of China) as a sign that a large switched on investor has done its research and sees this as an area for good long-term return on funds invested. Electric vehicles are coming, all the major car companies and many governments have put in place action plans to ensure that occurs.

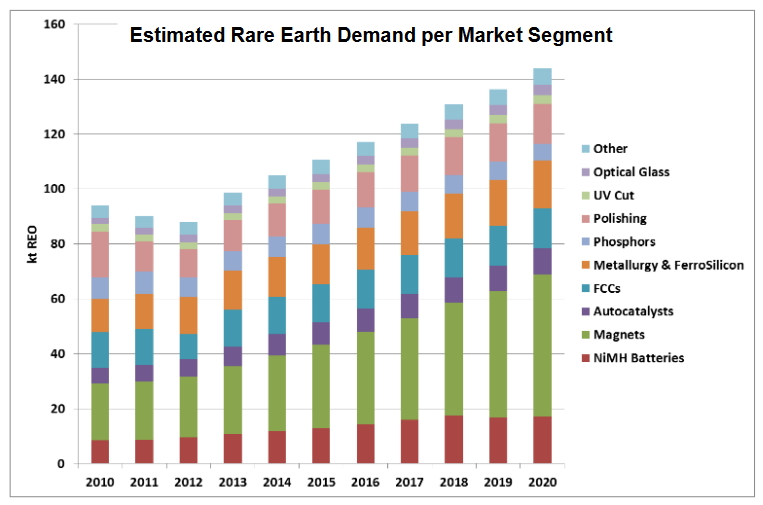

The major driver of rare earth prices should be the growing demand for electric vehicles (EVs) where some rare earths are critical in producing the powerful magnets required in the electric engines. Note these electric engines are a proportionally tiny cost in an EV (the largest individual cost is the batteries).

Rare earths have a very strong demand profile looking forward, but it is China’s tight control of the sector that has seen rare earth prices trade where most miners are losing money.

As Deng Xiaoping, one time paramount leader of China, said in 1992, “The Middle East has its oil; China has rare earth.”

What are rare earths?

The term rare earths (RE) or rare earth elements (REE) refers to a group of 17 chemical elements; the 15 lanthanides plus 2 others. Rare earth elements are often processed into rare earth oxides (REO). Thus there are 3 names which, for our purposes, are largely interchangeable. Despite their name, rare earth elements are fairly plentiful in the earth’s crust.

Whilst REEs might be plentiful, they are found mixed with each other and with non-REE materials. It is difficult, read “expensive”, to get the pure elements from the ore which is dug out of the ground. Additionally, processes used to extract the elements can cause environmental problems if not carried out with appropriate safeguards. For these reasons, it is difficult to find REE deposits which can be mined and separated economically.

Another notable characteristic of REEs is that many have tongue-twister names such as dysprosium, praseodymium and ytterbium.

What are rare earths used for?

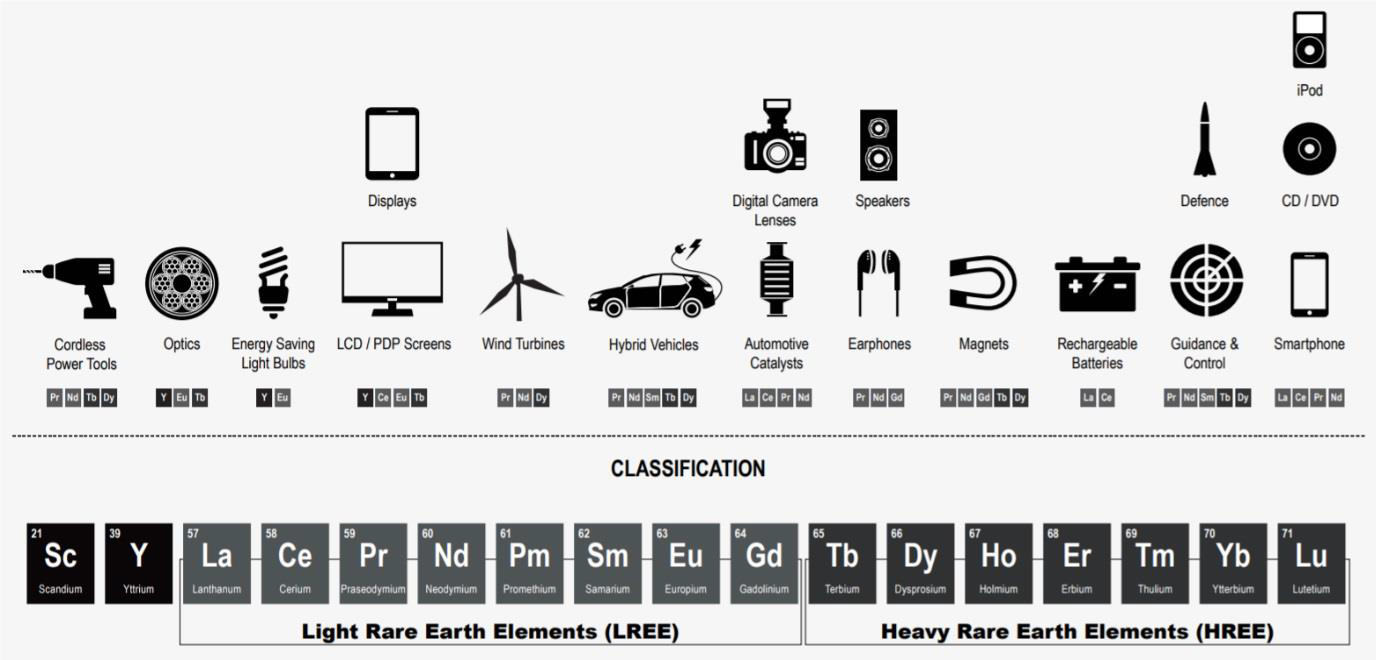

Rare earths have many uses, from everyday items such as catalytic converters in cars, fluorescent tubes, televisions and smart phones to some unexpected items such as self-cleaning ovens and lasers. (See graphic on next page).

Perhaps of greatest interest, particular rare earths are used in strong permanent magnets. These magnets can be made to be incredibly strongly magnetic and/or very small. Such magnets are used in electric generators and electric motors, as well as in small speakers (such as headphones), robots, and many other devices.

Discussions around REEs in the US always mention their use in defence, including guidance systems.

The two notable rare earth elements used in magnets are neodymium (Nd) and praseodymium (Pr). Dysprosium is also used, though in much smaller quantities.

Electric vehicles and wind turbines both use magnets containing REEs.

Uses of rare earth elements [China Water Risk report]

The rare earth market [1]

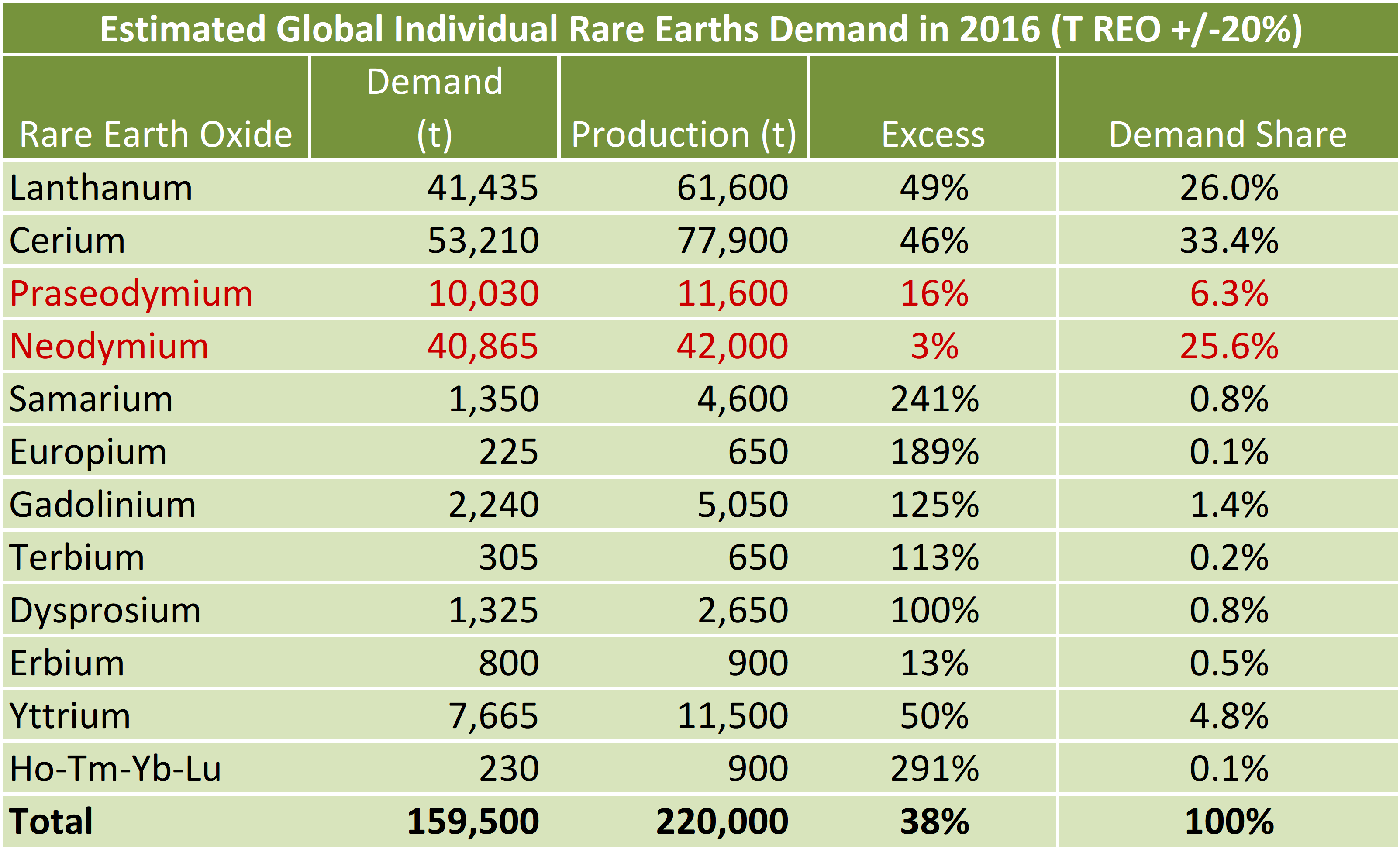

Mining and purification of rare earths produces a set of REEs, the composition of which depends on the particular resource. This can result in the over-production of certain REEs and under-production of others. Details of one year’s production demonstrates the point; the table below shows that a total of 220,000 tonnes were produced against total demand of only 159,000 tonnes. The over production was necessary in order to meet demand for the magnet rare earths.

Global demand by rare earth element

From the table, cerium which is used in fluorescent tubes, had production which was 146% of demand. At the same time, demand for neodymium (used in magnets) was only just met. See the table to the left for more detail.

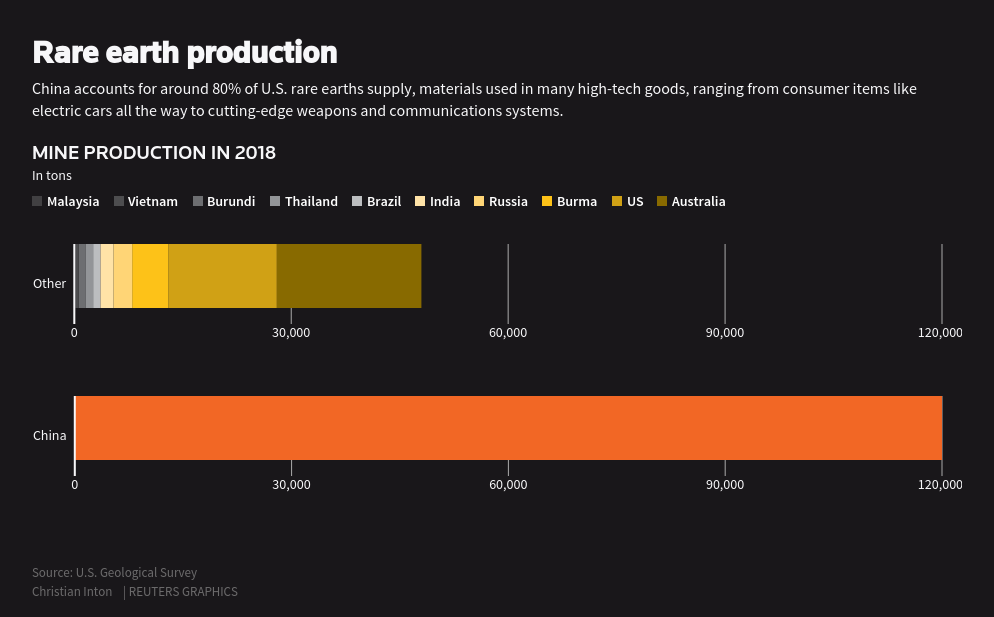

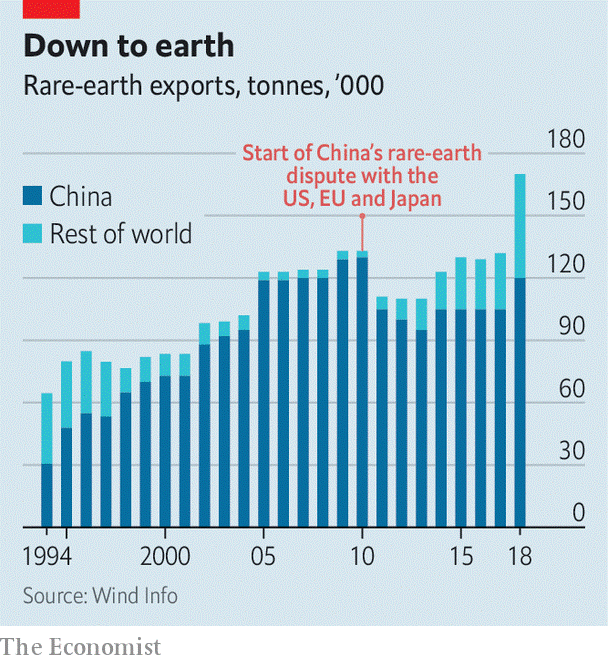

China dominates the rare earths markets with 85% of the global market in 2017. China is also dominating parts of the downstream (product) markets with, for example, 80-85% of the permanent magnet market [Peak]

Rare earth exports by year; China and rest of world [Wind Info/The Economist]

Rare earth exports by year; China and rest of world [Wind Info/The Economist]

As noted above, while there appears to be a surplus of production over demand, that is the case only when rare earths are viewed in total. The magnet rare earths, neodymium (Nd) and praseodymium (Pr), were in surplus by 16% and 3% respectively for the year in question.

It is thought that China has a large “legal” supply and a large “illegal” supply. It is calculated that illegal production in 2016 may have accounted for 110kt of the total global production of 220kt.

Since then, China has been working on improving rare earth production, including reducing the environmental impact of rare earth mining as part of its 13th 5-year plan.

Those changes may be biting given that in 2018 China imported 41,000t of rare earths, because the crackdown was limiting domestic output. [Reuters/Kitco].

Nevertheless, according to Professor Dudley Kingsnorth of Curtin University, projects outside of China have not advanced because of China’s vast production, underpinned by cheaper labour and less stringent environmental regulations.

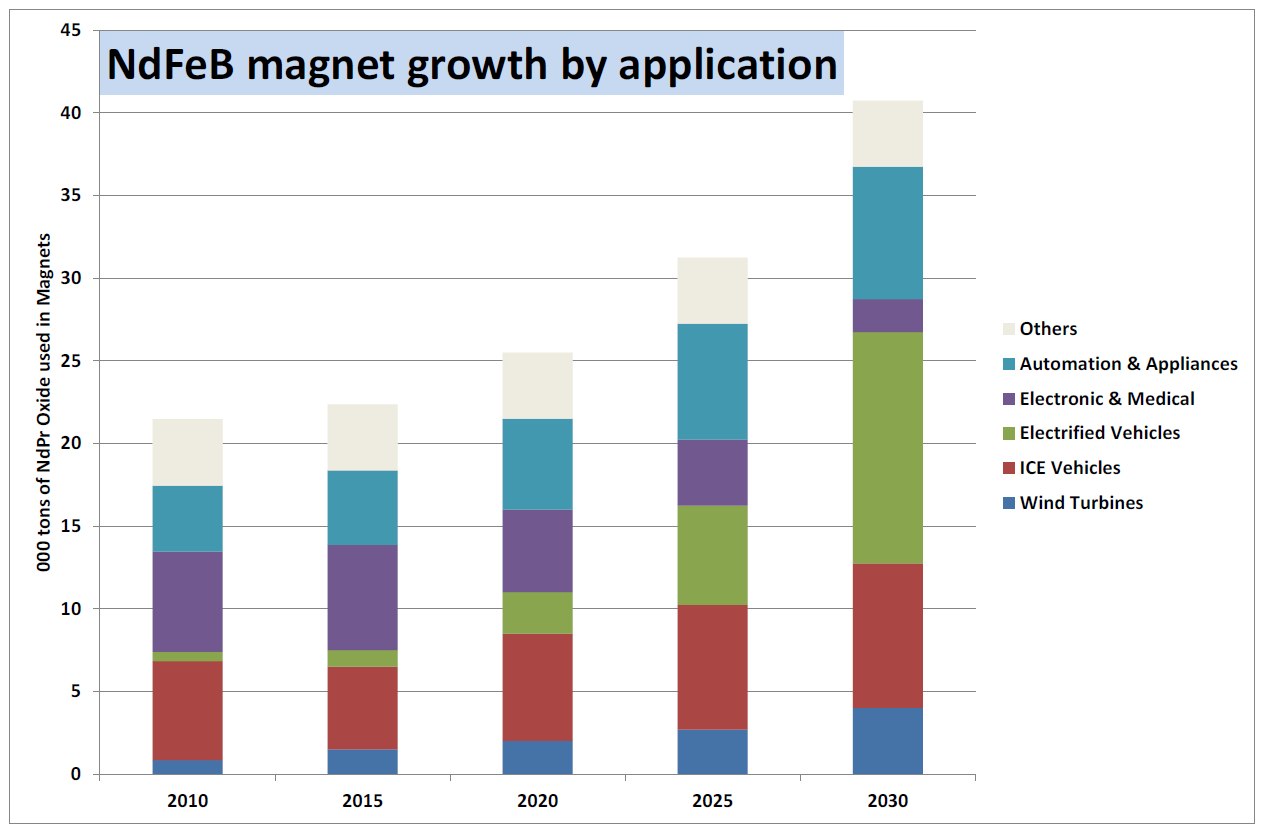

Actual and forecast demand for rare earths by use [Lynas Corporation]

Actual and forecast demand for rare earths by use [Lynas Corporation]

Actual and forecast demand for neodymium magnets [Lynas Corporation]

Rare Earth Mine Production [US Geological Survery / Reuters]

Prices

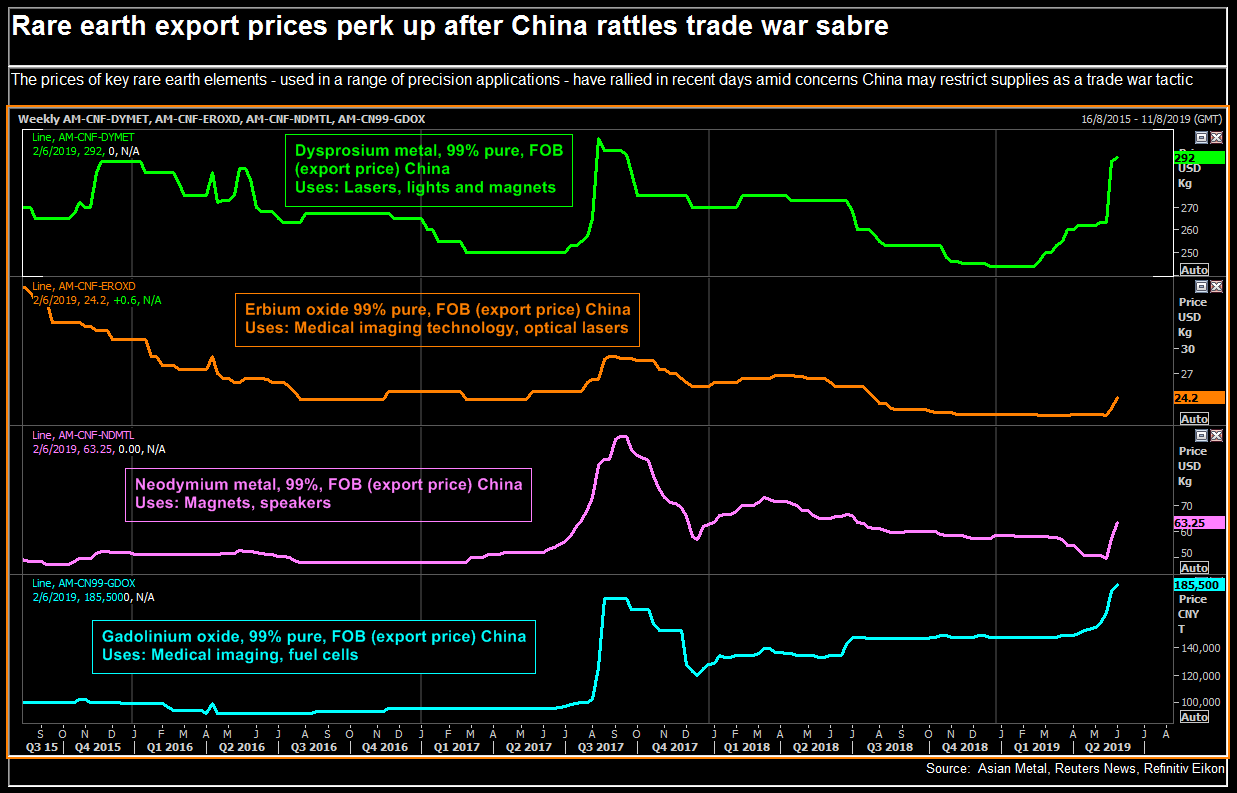

Rare earth prices have been historically low, although have been increasing recently as talk of China holding back exports grows in the wake of the China-US trade war (see chart below).

Note that, as with demand, prices vary greatly among the rare earth elements. The magnet rare earths, Nd and Pr, are in the middle of the price range.

At the cheap end of the price range are lanthanum, cerium and yttrium, the demand for which does not meet supply. At the high end of the price range are terbium, europium and dysprosium (this last one is also used in magnets but in tiny quantities).

It would appear that rare earth prices have been held artificially low by China in order to control the markets for both rare earths themselves and for many of the components in which rare earths are used, batteries for example.

Low prices have meant that it is uneconomic for new mines to be established. The recent price spike will need to be maintained and track higher to see new mines get funded.

Our concern however is that this spike is driven from speculation that China may restrict supply due to the current trade war with the US. We see that as a very low risk so are cautious about the recent price spike leading to lots of new production. Note that the US imports under 10% of global demand.

However, we do see that over time increasing demand must take prices higher.

Rare earth prices rising since trade war entanglement [Reuters]

Processing

Refining mined ore into rare earth elements is difficult, expensive and environmentally challenging. In addition to creating pollutants it is potentially radioactive. It seems that this is the aspect of the overall process which producers find most difficult to deal with.

China’s rare earth-induced environmental problems appear to stem from the processing step.

Lynas, the Australian miner which is the largest non-Chinese REE producer globally, has been processing its ore in Malaysia but that has run into problems with Malaysian government concerns over waste disposal. Plans to conduct initial processing in Western Australia prior to final processing in Malaysia have been proposed. There has also been discussion of Lynas processing its ore in the US. [Reuters].

Catalysts for change

Demand seems certain to increase in the coming years with the growing number of electric vehicles being produced and with increased wind turbine installation.

Electric vehicles each use 0.5 – 1.0kg of Nd/Pr more than an internal combustion engine vehicle. This is not much, but if 10m electric vehicles are produced p.a. (and some forecasts are much higher than that), the numbers get large. 10m x 0.75kg (say) = 7,500t of Nd/Pr. 2016 production of Nd/Pr was 54,000t, so a meaningful increase.

Manufacturers such as Volkswagen and Toyota have announced that they will be producing more and more electric vehicles each year.

In 2018, 95.6m motor vehicles were produced. If this production swings strongly to electric vehicles, as it seems it will, the rare earth demand figures above could become much larger: If 50% of vehicles produced were electric 36mt of Nd/Pr would be required.

Wind turbines of the direct drive type (which industry seems to be moving towards) use hundreds of kilograms of Nd/Pr each. Clearly, this is an area which might use a lot of rare earths in future if wind generation becomes the norm.

Another factor is that China has plans (including the 13th 5-year plan) which aim to stabilise the market as well as reduce environmental damage. If production is reduced in China, while global demand increases, this could lead to large price rises.

China’s jump in imports in 2018 (to 41,000t) we believe indicates its own production is struggling to keep up with demand and it is having to start to import material. It may also be the case that, by importing REEs, China is simply seeking to tighten its grip on the global rare earths market.

Recently, rare earths have been brought into the ongoing trade tensions between the US and China. China has suggested that its exports of rare earths may be curtailed if the tit-for-tat trade restrictions and tariff increases continue.

Regardless of the current trade tensions, it is likely that businesses relying on a supply of REEs will be uncomfortable with that supply being dependent solely on China. This should give impetus to the development of non-Chinese assets.

Finally, Wesfarmers’ takeover offer for Lynas Corporation has added interest to the area and added further credibility to the investing theme. A well-resourced business with a large balance sheet moving into rare earths certainly fuels activity.

Rare earth investments

We have looked at several opportunities in the rare earths space, one in particular though stands out to us, Peak Resources.

Peak Resources (PEK on the ASX) has proven up an REE deposit in Tanzania, the Ngualla Project. Peak is advancing the asset towards production; however, they are pre-construction of the mining/production facility. Points on Peak:

- At its current price around $0.04 its market capitalisation is just over $30m.

- A globally strategic asset. It has been referred to as the best undeveloped REE deposit globally. It is one of the world’s largest and highest-grade neodymium (Nd) and praseodymium (Pr) deposits (these are the magnet REEs).

- An estimated 26-year operational mine life (based on just 22% of the mineral resource).

- Spent over $20m on its bankable feasibility study, which is due to be released in April 2017.

- Due to the favourable host rock and low stripping ratio, PEK should be in the lowest 25% of cost producers globally.

- Refining of the ore will take place in Tees Valley, UK. Planning permissions and environmental licences are in place. Peak has an option over a 250-year lease.

- Has de-risked the project through an extensive pilot plant operation and testing (over $4m spent).

- Strong management team with extensive operational and commercial REE experience.

- Strong financial and development partners through Appian and IFC (arm of World Bank)

- There continues to be difficulties for miners in Tanzania after legislative changes which, as a whole, seek greater reward to the country for minerals mined. They include a free-carry of 16% or more for the Tanzanian govt, clearing fees on exports and restrictions of exports of unprocessed ores.

- Peak has met with the Tanzanian Minister for Minerals. It appears that Cabinet Papers relating to Peak’s application for a special mining licence are prepare and are expected to be received positively.

Peak’s Nd/Pr makes up 34% of their expected total output (Lynas: 31% in FY2018). This compares to the global output average of 24% of total rare earths. Demand for Nd/Pr is 32% of total RE demand. More importantly, Nd/Pr represents about 85% of Peak’s anticipated sales revenue. Therefore, Peak’s mix of rare earth elements is very favourable for the expected future demand.

The fact that Peak has detailed plans (along with licences, land access, etc. for a refining operation in the UK is a major benefit – refining is a critical part of the puzzle and many miners don’t tackle it.

There is also strategic value in Peak’s resource. With increasing demand for electric vehicles and major car manufactures spending billions on their development, manufactures will want to reduce risk from sole supply from China.

Peak plan to build a US$200m plant in Tanzania to produce a 45% high grade concentrate. This will then be shipped to the UK where they will build a US$165m facility to produce the final rare earth oxide material.

Conclusion

The rare earth market is an interesting one. It has a dominant player in both demand and supply, China, which may be undergoing substantial changes. Those changes may restrict future supply. At the same time, the price of rare earths has been low.

A strong case can be made for rapidly increasing demand of rare earths, driven by forecasts for strong increases in production of electric vehicles – as well as increased production of wind turbines, robots and other products.

Concerns have been expressed about the situation of global supplies being so dependent on China. These concerns have come into sharp focus with rare earths becoming a bargaining chip in the current trade war between China and the US.

There is every likelihood that the rare earths market will “take off” sometime over the coming years. As we said in 2017 when we last wrote about rare earths, picking the timing of that change could be difficult. Nevertheless, all of the factors which we discussed as being positive for the rare earths market in 2017 still hold true today – and some of those factors have become more pressing.

We consider that investment in rare earth developers only stacks up if/when they have solid plans for not only obtaining ore but, critically, processing that ore into saleable rare earth oxides.

This requirement severely limits the range of possible investments. For now, we are likely to restrict our investment to Peak Resources.

We will, however, be watching this area more closely in an effort to pick the start of any meaningful ramp up in prices and activity.

[1] Much of the information in this section comes from the Curtin University presentation to the 12th International Rare Earths Conference in Hong Kong 8th-10th November 2016. This is slightly outdated but nevertheless demonstrates the basics.